Why Shooting 'Cunningham' in 3D Was 'A Massive Production for Every Shot'

Alla Kovgan's 3D re-staging of Merce Cunningham's most iconic performances bursts out of the frame.

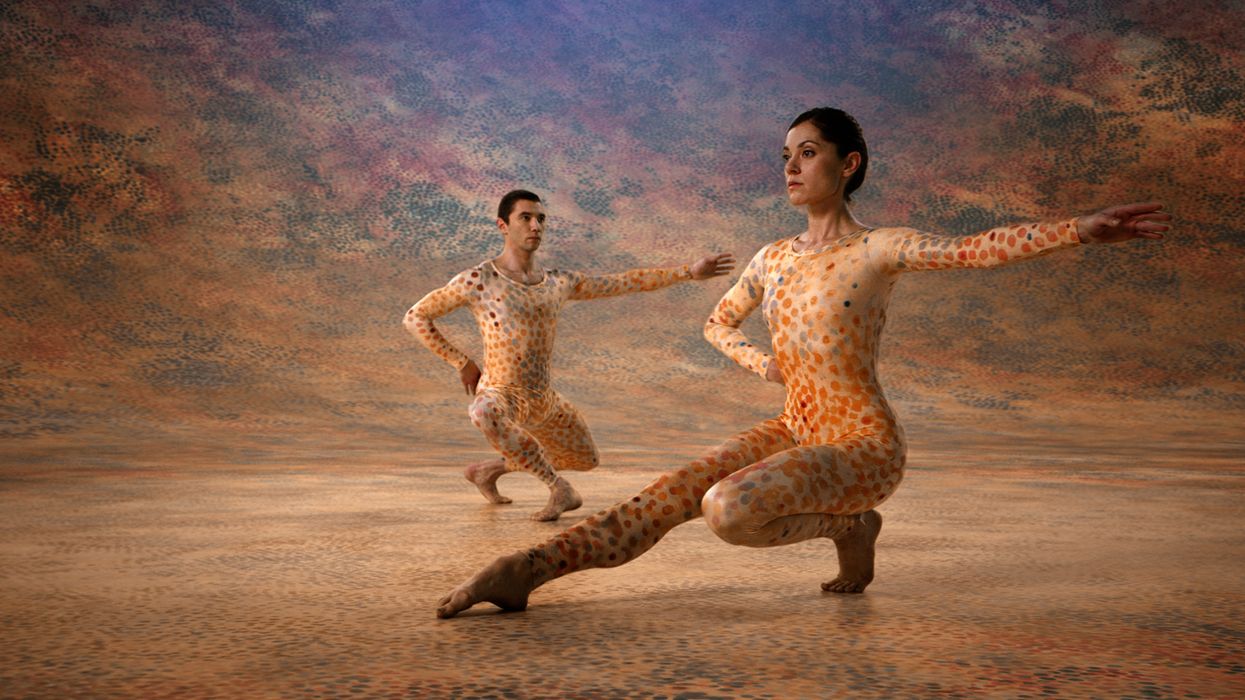

Watching Cunningham, it's hard to believe Merce Cunningham didn't choreograph his dances for the 3D screen in the first place. Alla Kovgan's film is an immersive documentary that puts you right in the center of the modern dance legend's most visionary works. The dances overflow from the frame—you're transported into a universe where the immaculate choreography radiates off of the dancers' bodies and into the spaces they inhabit, creating a narrative of movement that's more complex than the sum of its parts. Kovgan stages fourteen of Cunningham's most iconic dances in airplane hangars, palaces, dense forests, and rooftops. There is a sense of aliveness, of inhabiting, that transcends the power of dance as seen from a stage. In three dimensions, and on film, the dances themselves, ephemeral by nature, are rendered timeless.

No Film School sat down with Kovgan to discuss the entire process of shooting the dances in 3D, including elaborate pre-vis modeling, extensive camera operating rehearsals, and more.

No Film School: This film has been in the making for seven years. Where did it all begin?

Alla Kovgan: Well, I've done a lot of dance documentaries. I even did narrative films that are based on real stories about choreographers. Then, in 2011, a film came out named Pina by Wim Wenders, about the choreographer Pina Bausch, in 3D. I felt like there was something special in the 3D version of the dance-film collaboration.

3D has been around for a long time, but usually, it's used to a gimmicky effect. Here, there was something different. 3D is very good with working with space, and Wim did something that made you feel very close to the dancers—you almost could step inside the dance.

"Something neurological happens when your brain perceives 3D. Your brain works 30% harder."

Something neurological happens when your brain perceives 3D. Your brain works 30% harder. You feel the distance between people. Your kinesthetic empathy wakes up. You empathize with what's in front of you—you feel closer to people. It evokes an emotion that is not there in 2D. You have an experience. Something shifts in the way you engage with the material. Basically, your perception slows down. Since your brain is working harder, you allow yourself to watch fully.

Of course, 3D can be an absolute disaster, as I said before. Also, 10% of people in the world can't even see 3D [when the glasses are on].

Anyway, [when I was watching Pina] I was thinking that 3D works very well for dance. Then, I found out about a grant from the Rockefeller Foundation and Dance Films Association to make a film about New York-based choreography using 3D technology.

Kovgan: It all began in 2015. We did the pilot of Summerspace [a Cunningham dance]. There was an elaborate process because of CGI. We shot green-screen. I found some archival materials that nobody has ever seen, including one dance that was lost for 50 years.

Then, in 2016, we thought we were going to shoot. Financing fell through, and that's when we moved to Germany to raise money.

Making movies is all about talking about the film. Half of the time I was making the film, I was talking about it, trying to convince people that it's actually a worthy idea.

Finally, in 2017, we learned we were going to shoot. The dancers went to the studio to rehearse. Then, in 2018, we shot the movie. I edited it myself and finished in March 2019.

"Half of the time I was making the film, I was talking about it, trying to convince people that it's a worthy idea."

NFS: What was it about Merce Cunningham that captured your

Kovgan: I went to the last performances of the Merce Cunningham Dance Company, which shut down on December 31, 2011, at the Brooklyn Academy of Music. I hadn't thought about making a film about Merce before. I knew his work, but he's the kind of choreographer where you'd have 16 people going in different directions, so you can't frame a single shot. But during those performances, I felt in my gut that Merce and 3D have something to do with each other. That's because Merce is so amazing with working with space. For him, dance was all about organizing action in time and space.

I wrote to the Director of Choreography for the Merce Cunningham Dance Company, Robert Swinston, and said, "Let's make a film about Merce's choreography in 3D." He immediately said yes. He also brought on Jennifer Goggins, who became our director of choreography. It took quite a bit of time to convince everyone else that we should do this—but Robert really wanted to, and so it worked out. The Merce Cunningham Trust gave us the license. It took about a year to get the rights.

Kovgan: We started thinking about what kinds of things we were going to actually film. We decided to basically pick works [to perform], and then from those, we would pick excerpts to teach dancers, and that's the stuff that would be shot. Some of Merce's pieces were very well documented—there were videos of rehearsals and performances. It was still a very tedious process. It took about seven months altogether. We had six weeks of rehearsals, six days a week, six hours per day, with 14 or 15 dancers and some understudies. Jennifer and Robert taught this material to the dancers, and we also used this time for the rehearsals for the camera.

My director of photography [Mko Malkhasyan] came every day for a few hours, and we basically looked for ways to feel what we saw. Of course, we had seen videos and had all kinds of ideas, but there is nothing in comparison to seeing the work live.

"You can't cut from a wide shot to a closeup [in 3D] because it disturbs your vision and everything goes haywire."

Now, my DP was very generous—he didn't charge for this time. If we had paid everyone in this movie as much as we should have, it never would have happened. We would have gone bankrupt before we started.

Anyway, I had never worked with 3D before. I've never been scared of technology. I worked in theater—I did video projections for music bands. I know how to do multiple kinds of screen projection. Still, 3D is massive. There are a lot of technicalities that I had to learn.

Of course, we tried to track down people who worked on Pina because fundamentally these are the only people who understand anything about what we're trying to do. We watched a lot of 3D films, trying to understand: What is the language? What is there to explore? How do you edit in 3D versus 2D?

NFS: What is the difference between editing for 2D and 3D?

Kovgan: What I learned is that you can't cut from a wide shot to a closeup, because it actually disturbs your vision and everything goes haywire. So here's this very simple, classic part of film language that is destroyed. The best 3D film has no cuts. It's kind of like Russian Ark [laughs].

Kovgan: So, if you can't cut, what do you do? You just move. You come to your shot, the frame that you want. So you don't cut to the closeup, you come to closeup. Oftentimes, 3D is shot on a wide lens for this reason.

We did a 3D test in 2013, and without that, it would have been really difficult to understand all these things.

NFS: How did you and your DP conceptualize Merce's ideas and translate them into the camera movements?

Kovgan: Yes exactly—the film is not about capturing dance. It's about translating Merce's ideas into cinema. It's this idea of how do you make cinema out of dance? Merce didn't like to say what his dances were about. He liked to kind of pose a physical question: "This dance is based on the idea of falling. This dance is based on the idea of togetherness. This one is based on the concept of layering." Then, he'd let you, as an audience member, interpret what you see.

How do we translate these ideas into cinema? If you think about a dance based on the action of falling, you start thinking about heights, and then you start thinking about Vertigo. A rooftop! The locations became metaphorical and were a way to amplify and translate Merce's ideas into cinema.

"It's a process of teaching the Steadicam or crane people the choreography of the camera in relation to the choreography of the dance."

You'd never think about filming anything on a stage. Why would you? Unless it's part of the narrative. The only time we use stage is when John Cage and Merce Cunningham gave their first concert together. That's it. Everything else has no stage.

NFS: How did you find your locations?

Kovgan: Well, that is an interesting answer. First, we found all these locations in New York City, and we storyboarded the film for them. Then, we couldn't raise money here, so we had to go to Germany [for regional funding]. We filmed everything in Germany everything except for two pieces—the rooftop scene, and Summer Space, which we shot in France as a pilot.

NFS: Can you take me through one scene, in terms of pre-viz, choreography, and then, eventually, filming?

Kovgan: Let's take the woods scene. This one was about layering. If you look at the dance, people are working on different planes. There's a conversation constantly between the dancers, the background, the foreground, the middle ground.

Kovgan: So, once you pick a location, you have to study it. You have to see what the light's doing. These days, there are all these gadgets so you can see where the light is going to be at [a given time]. But actually, if you really want to shoot at that particular time, you've got to go there and see what happens. So we came to the locations several times, measured the light, and then modeled it.

NFS: With computer software?

Kovgan: Yeah. Just like what the architects use—CAD programs. You model the location to scale, and then you put it into previz, which is a software. Then you model your dancers, and then you basically reproduce the choreography within the software. You end up with an animatic of everything. You can model the camera moves with a Steadicam. You can set the lens you are working with. You can pretty much completely pre-visualize your shoot. Since we only had 18 shooting days, that's the only way we could shoot with this crazy schedule.

"One Steadicam operator on the film was really gifted. He was like a dancer with a camera."

Going back to the forest, so, we measured it, then we modeled it. Once you do this animatic thing, you can show it to the crane operator and to the Steadicam operator but they don't actually understand what they're looking at. You show them the video of how it looks on stage. You show them the video of how we shot it in the rehearsal so they have it. Then you show them the storyboards, and they can't imagine how are they going to deal with the speed of the dancers. What happens is that it's a process of teaching the Steadicam or crane people the choreography of the camera in relation to the choreography of the dance.

NFS: Movement by movement.

Kovgan: Yeah, just phrase by phrase. Crane [operators] cannot remember more than 40 seconds of material at a time. There's nothing you can do. We worked with the crane operators from Pina, and in that film, they actually had music. They remembered Stravinsky's music and then they remembered their own movements. Here, there's no music, so they were completely lost. With Steadicam operators, it was a little better because with Steadicams you have to move with your body, and they kind of choreograph themselves. One Steadicam operator on the film was really gifted. He was like a dancer with a camera.

Kovgan: It goes like this: First, you ask the dancers just to walk [the piece], so the operators can see the trajectory of the movement. Then they do it at half speed, and then the Steadicam operator organizes himself in the space. Sometimes he's going 360 degrees. And don't forget that you have to move all of the equipment—you have to take everything out, and you have to hide it so that we don't see it in 360.

Also, remember, the rig is very heavy. It's two cameras strapped together. It's like you're going back to the 1950s, with the 70mm giants. This is a complicated thing. Sometimes the operator needs to do it with a small camera first just to learn. Then he does the walkthrough with the rig. Then, finally, you do it at full speed. Then we shoot.

"The concentration that's required from everyone on set is quite amazing."

Now, sometimes dancers will say, "I can only do this shot five times." Sometimes just once. It is this incredible moment where things have to come together. The concentration that's required from everyone on set is quite amazing.

After we shoot, we review. There are six pairs of eyes: myself, the DP, the stereographer, the Steadicam operator, the crane operator, the focus puller, the director of choreography. Everybody looks for their own thing. The Director of Choreography is looking for the performance. That's all she's looking at. She doesn't care what happens in the frame. The DP is actually mostly looking at light, and what happens with light. I look at the framing. The stereographer looks at where the dancers are in space for the 3D effect.

It's kind of a massive production for one single shot. It all has to align. There's going to be only one take, usually, when the choreography of the camera and choreography of the dancers align. When that takes happens, we all stop and we look at it. Sometimes the dancers can offer an interesting suggestion on how they can position themselves.

Then, finally, we do the sound take. When everything is shot, we shut everything down and we do sound just of the dancers' feet. We'll put eight mics around the set. Dancers hate it, but I think it's really important to give life to the movement. It's worth it.