'JFK': How Oliver Stone and Robert Richardson Shot the Scariest Political Movie Ever

Oliver Stone arguably peaked with his Oscar-winning JFK, which was released 28 years ago. Here's why this political conspiracy thriller still holds up.

When JFK was released in December 1991, it was a sensation.

Suddenly, the conspiracy theories that had been whispered about since Kennedy's assassination in 1963, they reemerged into the mainstream. New books, articles, and television specials flourished.

The film, ingeniously directed by Oliver Stone, was a certifiable blockbuster (after a somewhat rocky start) and was soon nominated for eight Academy Awards, including Best Picture and Best Director and won two, for Best Cinematography (Robert Richardson) and Best Editing (Joe Hutshing and Pietro Scalia).

At a time when George Bush tried to extend the sunny conservatism of Reagan, JFK was calling into question virtually everything about our supposedly truthful and transparent government. Long before the dangerous conspiracy theories of Alex Jones, Stone introduced a gentler, but still terrifying, paranoia back into the mainstream by crafting the scariest political movie ever.

Much of what makes JFK such an unsettling watch is the way that Stone put the movie together and Robert Richardson shot it.

Richardson got his start working on smaller, counterculture movies like Breakin' and Alex Cox's Repo Man. He had already made a handful of movies with Stone, including Wall Street and The Doors (which, astoundingly, came out the same year as JFK). With JFK, though, the collaborators pushed each other further and farther than ever before.

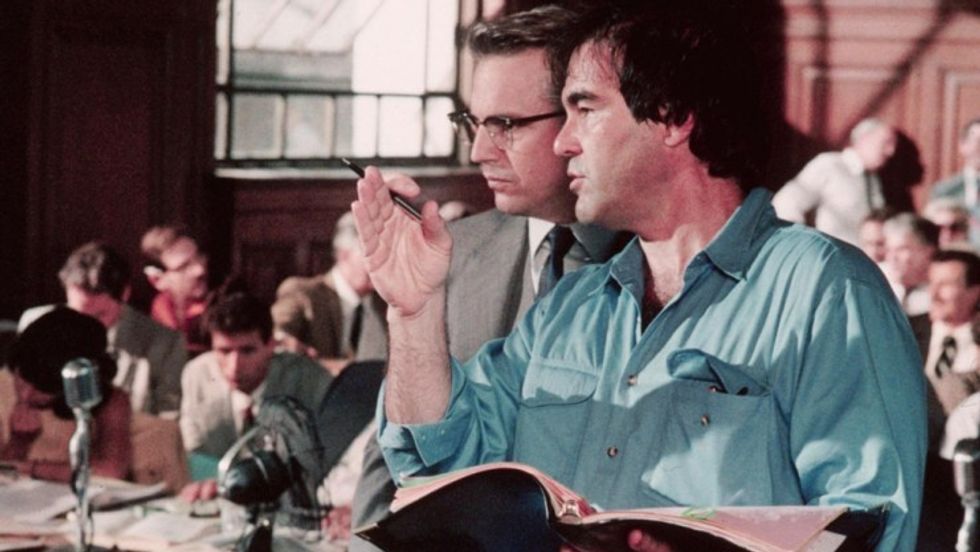

One of Richardson's most notable stylistic flourishes, his "hot tables" (where tables or other surfaces are illuminated by some unseen spotlight), takes on a different meaning here. It's not some aesthetic embroidery; instead, it turns any table, anywhere, into an interrogation room. (This was, after all, a movie about a New Orleans district attorney played by Kevin Costner, who reopens a criminal investigation into the JFK assassination.) JFK's deep south setting allows Richardson to intensify this sensation; everyone is sweaty and Richardson trains his camera to lovingly catalogue each droplet.

Instead of a straightforward thriller, which it could have easily taken the shape of, Stone allows himself flights of fancy, working in harmony with Richardson to create an uneasy, slippery feeling. As Costner and his investigators search for clarity, things become more obscured, shadowier.

Another great example of the way that Stone and Richardson mix and match formats and styles for greater dramatic oomph comes earlier in the film, when Costner is reading the official testimony of a railway worker stationed behind the so-called grassy knoll. The worker says that he saw shady characters emerge from the railroad tracks. (These characters are later shown to be wearing crisply tailored new clothes.) The sequence is rendered in grainy black and white, perfectly mimicking Costner reading the report (since, you know, the report would be black text on white paper).

At the end of the sequence, there's a hallucinogenic blur of color, and it's unclear if it's a re-staging of the assassination or Stone taking the Zapruder footage and warping it almost beyond recognition. In the next scene -- Costner awakes, violently, from a nightmare. The nightmare is real; we're all in it.

But there are also subtler ways that Stone and Richardson draw you in.

There's a moment when they're interviewing Jack Lemmon, who plays a confederate of a private investigator involved in the conspiracy. Stone and Richardson set up the scene incredibly; they're chatting at a greyhound track. They've established a shadowy figure in sunglasses in the stands and, for even more intensity, cut away to slow motion shots of the dogs racing, with sand flying up towards camera. But one of the greatest, most invisible moments comes when the camera is so close to Lemmon you can only see his eyes.

As an audience member you lean in, and you can tell that the dialogue was recorded live (this wasn't filmed in this fashion to cover up some bad ADR), because Lemmon's movements match his dialogue. It's fascinating and so unnerving. And if you weren't looking for it, you wouldn't pay much attention.

Flashier is the infamous sequence where Donald Sutherland, playing a figure codenamed X, discloses the political atmosphere that led to the assassination and carried through after the fact.

Stone and Richardson use a variety of film stocks and styles, combining newly filmed footage with historic footage of actual historical figures. In a weird way, this scene (scored ominously by John Williams' music, also nominated for an Oscar) exemplifies what makes the movie so freaky and powerful: With the mixture of real footage and newly filmed stuff, the message is clear, you can't tell what is true and what is fake.

As Costner says, we're through the looking glass here. You can't even believe your own eyes.