Understand the Origins of Cinema with This Important History Lesson

The art of cinema started long before the motion picture.

We have a natural curiosity and obsession with light. As we congregate around a blank screen in a darkened room, the light source shows us a story that entertains us, resonates with us, and inspires us to think differently about the world.

Our desire to experience life through abstraction to make sense of our state of existence is why we are drawn to this light. This is how it has always been since the dawn of visual storytelling.

The history of cinema is extensive, and there is a lot to cover. What we are focusing on here is how light has shaped motion pictures and continues to influence how we make films in the modern age.

Shadow Puppet Theater

Shadow puppet theater was the first glimpse into what modern cinematography would be. The art form featured handmade jointed puppets illuminated behind a large thin cloth that would perform narrative scenes for an audience. The puppets were held close to the screen and lit from behind while the puppets were manipulated with attached canes.

The use of creative light and dyed leather to bring color into the puppetry influenced how the audience interacted with the stories. Not only did the audience resonate strongly with these stories and performances, but the stories conserved the heritage of the storyteller while honoring ancestors.

These projections became the fundamental process of cinematography. The specially crafted visual experience could influence how the audience understood and connected to what they were watching.

Shadow play is still regarded as an important cinematic art form, with Manual Cinema using shadow puppetry in Nina DeCosta’s Candymanas a way of conveying a well-known urban legend that is rooted in systemic violence and racism.

The Camera Obscura

While shadow puppetry is the root of cinematography, the closest, tangible item that could be compared to the invention of film and the culture around it is that magic lantern. The magic lantern utilized a form of early projection that was originally established by the camera obscura.

The camera obscura is a device that reflects inverted light through a pinhole onto a mirror and through lens focus, creating a projection onto a flat surface. Dark rooms would be filled with an image projected by the natural sunlight that many draftsmen and artists would often use to trace certain objects or to copy their work.

While most cultures experimented with light and reflections, the camera obscura opened up the discovery to a wider audience, revealing that an image could be imprinted onto another surface through light. Artists would paint images onto the mirror, then project them for an audience to marvel at. It was an awe-inspiring invention.

The Magic Lantern

The camera obscura would eventually be developed further to expose light-sensitive materials to capture the projected images while still being used as a form of entertainment for the public.

As the photographic camera was slowly being invented, the magic lantern was created due to the discovery of slides. By using sunlight as the main source of light to project inverted images painted onto a mirror, the image could be projected onto a large, flat surface.

Unlike the camera obscura, the magic lantern allowed for these glass slides to be inserted and removed by the operator. An infinite amount of images could be viewed through the magic lantern, and the portable slides allowed the operator to create lengthy visual shows.

As these magic lantern shows started to travel across the country, Étienne-Gaspard Robert (also known as Robertson) pushed the limits of the magic lantern to create an immersive spectacle of horror and mysticism with illusions of the resurrected dead. Known as "phantasmagoria," Robertson's shows used multiple magic lanterns modified to have wheels, allowing a crew member to create the illusion that a projection was moving by pushing or pulling the magic lantern closer or further from the screen.

Not only did Robertson build a magic lantern that could move, but he could project layers of images all at once. Robert included sound effects in his shows and manipulated the lenses of the magic lanterns.

One of Robertson's most impressive accomplishments was his ability to create a background with a static magic lantern placed behind the screen while another magic lantern in front of the screen to create a foreground. This technique known as rear-screen projection would be used 250 years later in Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey. This technique also would inspire Disney’s usage of cel animation.

The Daguerreotype

Robertson’s visceral horror shows had created an experience unlike any other. But then the first photograph had been taken with a camera obscura, rendering the magic lantern as a soon-to-be obscure device.

Nicéphore Niépce had recorded an image from a camera obscura using the process he invented called heliography. Niépce discovered that when an asphalt substance is exposed to sunlight, the substance hardens and leaves a residue that, when rinsed with lavender oil, leaves an image that is just visible. French artist and chemist Louis Daguerre met with Niépce to discuss the process, and the two secretly designed a camera and improved Niépce’s process.

Daguerre developed a camera that had a copper base with a silver plate on top, on which the image would be exposed. After polishing and treating the plate to give it a mirror-like finish, the plate was covered in a compartment to react with fumes from iodine and bromide, making the plate sensitive to light. The plate was then placed in a box and then placed into a camera obscura. The subject would then sit perfectly still for several minutes while the lens cap was removed to allow light to slowly seep in and react with the silver plate. The plate was removed and washed with sodium solution and cleansed, washed with gold chloride, and heated so the image was fixed onto the plate without fading.

Known as the daguerreotype, the invention of the photography camera allowed people to see themselves as they were. This was the first time people were allowed to express themselves objectively, solidifying their existence through a new medium that reflected the world around them.

The Embrace of Visual Storytelling and the Zoopraxinoscope

While the daguerreotype allowed for objective realism to exist in a new, tangible medium, these negative and positive images could not be projected onto a screen.

In 1841, William Henry Fox Talbot used light-sensitive paper coated with silver iodide, which darkened in proportion to its exposure to light. This process created an acceptable negative, allowing artists to make multiple copies of the captured image.

The stereoscope was invented for a user to view a stereoscopic pair of separate images, depicting left-eye and right-eye views of the same scene, as a single, three-dimensional image. Like Robertson who used movement to create depth in his optical shows, the stereoscope created the illusion of movement and mimicked reality. Audiences were in awe of people and places that they have never seen before, creating a level of realism that was exciting.

Slowly, people began to want the images to relate to one another, creating a visual story that added to the entertainment. Cinematic continuity became the norm, and the camera operator could explain to the audience why the camera would move or change directions as they change the slides. This level of complexity was embraced through visual storytelling.

As the slides started to connect and tell a story, Alexander Black, an art editor for the Brooklyn Institute of Arts and Sciences, developed a technique that suggested motion through various slides of photographs. Actors posed in various positions so when the slides dissolved into the next one, it appeared as if the actors were moving. Black’s “Picture Play” titled Miss Jerry consisted of 250 slides that presented a 90-minute narrative on screen.

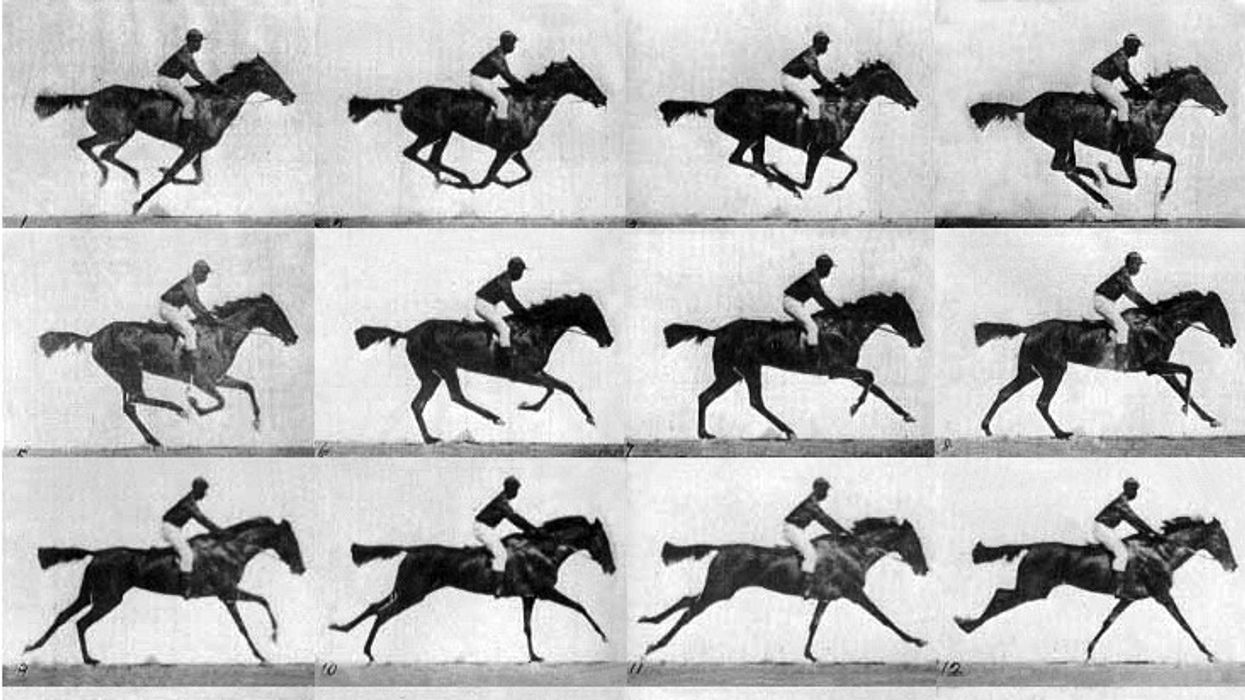

While Black is credited for his role in the development of motion pictures, the first official motion picture was Eadweard Muybridge’s The Horse in Motion. Originally hired to take photos of a horse for horse gait analysis for Leland Stanford, photographer Muybridge developed a technique that set up 24 cameras across a large backdrop. As the horse galloped in front of the cameras, it would trip a wire that caused a spring mechanism in each camera to activate. The cameras, whose shutter speed had been set to take a photograph a 1/2000 of a second, would capture the image as the horse moved.

Fascinated with the images, Muybridge invented a disc that could be rotated while projecting the images on a screen without an interruption. Known as the Zoopraxiscope, the 24 frames per second perspective and continuous projection created a moving image that replicated real-life motion.

While cinematic technology has long surpassed Muybridge’s Zoopraxiscope, it is amazing to look back on the origins of cinematography, editing, and filmmaking. Each invention was influenced by a previous marvel that entertained the masses. Inspiration is the catalyst for progress. Filmmakers today are borrowing from the techniques of great filmmakers from the past, and creating new meaning through the same techniques.

We are constantly inspired by each other to create and push the boundaries of what is possible. Who knows what groundbreaking, life-changing technique or invention you could create by just learning from the filmmakers of the past and present?

Source: The Cinema Cartography