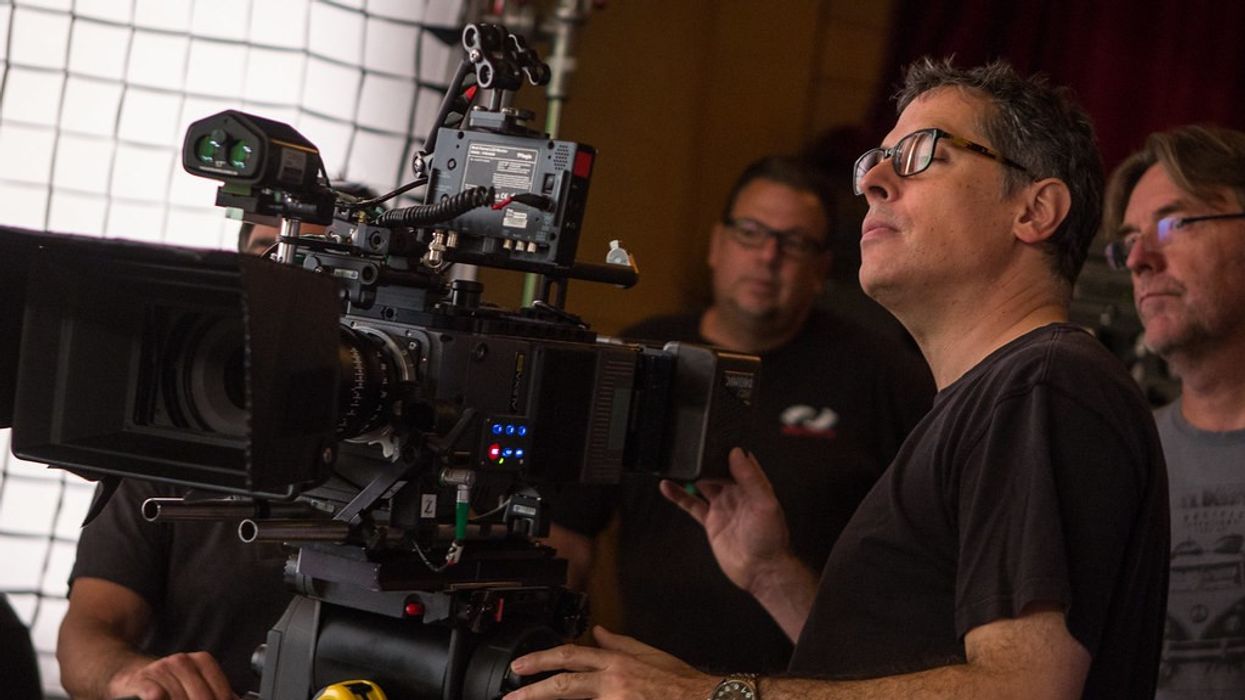

Rodrigo Prieto Tells Us Everything We Want to Know About How They Shot 'The Irishman'

The celebrated DP takes us deep behind the scenes of Scorsese's mob epic.

Truly old-school auteurs weren't huge fans of a moving camera. They might glue their camera still for no better reason than a novice might throw theirs out a window. Martin Scorsese never neglected the vocabulary movement granted him. As more tools presented themselves, he tried them, but always made sure they spoke.

For The Irishman, Netflix financing afforded Scorsese new tools like the “Three-Headed Monster”, the three-in-one-camera rig that allowed him to digitally “de-age” his old collaborators Robert De Niro, Joe Pesci, and, for the first time, Al Pacino, in a century-plus account of the murder of Teamster leader Jimmy Hoffa.

This Frankenstein system consisted of two “witness cameras” that captured an Infrared map of the actors' faces for the VFX team rigged to a third primary capture camera.

His go-to DP of late, Rodrigo Prieto, constructed these personalized tools in the film’s extensive prep. In scenes that did not require the digital “Three-Headed Monster,” Prieto switched to 35mm film. With all these cameras, he played in modes both still and fluid. When the film took on the mien of its reserved hitman Frank Sheeran, Prieto and Scorsese stuck to simple frontal frames and plain pans.

The signature Scorsese flourishes were reserved for energies in the film other than Sheeran’s, like the celebrity-like introduction of “Crazy Joe” Gallo, a sweeping crane shot with TV crews flashing the lens. But as the film relays the story through Sheeran’s first-hand account, the camera filters most of the affairs through his point of view. Outside influences on Sheeran motivate the more complex and lavish flourishes Scorsese allows in The Irishman, so as those influences die away the movement goes too. Sheeran becomes the only remaining element and Prieto dutifully cements his camera to the ground.

NFS: The Irishman’s camera language calls back to Scorsese’s earlier films and even your recent collaborations. That’s maybe inherent in any later film in a body of work, but was there a conscious effort to borrow some of that old language for specific sections of the film?

Rodrigo Prieto: There wasn't actually discussions of that sort, if this scene emulates this or that movie. It might have been something that was in Scorsese's mind that he didn't mention to me. But also I think he just has a way of seeing things as an artist that naturally permeates into his work.

The Irishman has similarities to his other movies, but Frank is more introverted. He's more of a reserved person. He even stutters and doesn't talk a lot. He doesn't find the whole gangster, mafia thing exciting. For him, it's a job, just as killing people and prisoners of war in the Second World War was.

Now the job is to be part of this group and rise in the ranks of the teamsters union. He has to strongarm people and become a hitman.

Frank is shot very simply throughout. So it was basing the language of the camera on the character, and I think that's something that permeates all of Scorsese's work. The camera, instead of doing big crane moves or tracking shots for Frank, would just simply pan.

Silence was shot very differently, and it was also meant to be from the subjective perspective of its main characters.

NFS: Why do we find Frank in the opening shot in his retirement home instead of starting on him?

Prieto: Right. I think part of it is even musical. I know that Scorsese had that piece of music in mind before we even shot. I think he listened to it while we were shooting. Scorsese asked me, while we were designing that and scouting the location, about the possibility of the camera going through other hallways and turning this way and that. But he wanted to keep it simpler, again, because of Frank Sheeran. That's why we start in this dark hallway and segue into the common room where we find him. He didn't want it to be too complicated. He wanted a sort of linear feel to it. And he also didn't want it to feel very stable either. The shot stumbles a little and he wanted to keep it that way.

It felt accurate to me to have space in a retirement home where older people have time. The camera just lingers. It's different later. There's a shot where Anastasia, this big hit that happens when he's in a barbershop in a hotel, where the camera does do a “Scorsese” thing. By the way, we stitched a studio shot of the barbershop we shot on a stage to a location, when the killers walk through the hallway and the camera goes around them and ends on some flowers. So, that's not Frank Sheeran. The camera behaves differently. That's murder.

There's the scene where he shoots Joe Gallo. That one we approached a little differently. That one is handheld inside Umberto's Clam House. But it's one shot, so instead of doing a bunch of coverage, getting the reverse on Gallo, the reactions of the bodyguard and all the people, we did it in one shot.

It's fast and violent and it's over quick. Again, that's the way that he approached these killings, unromantically.

"I did a lot of research into Kodachrome, Ektachrome, how they looked in print and how they looked projected. We did deep research on how these emulsions were made and how they reproduced each color."

NFS: Why are you using an ARRI Alexa platform for the “witness cameras” and a RED Helium for the primary capture camera and not vice versa?

Prieto: I came up with this idea of representing the different decades with different LUTs. The idea was based on a conversation I had with Scorsese where he mentioned he wanted a sense of memory and a home movie type of thing, but he didn’t want it to look like a home movie, Super 8, grainy, handheld film, or 16mm. So, I thought maybe a way of representing that was the still photography emulsions of different eras.

So I did a lot of research into Kodachrome, Ektachrome, how they looked in print and how they looked projected. We did deep research on how these emulsions were made and how they reproduced each color. So, we made LUTs for both film and digital to match. We obviously wanted it to be a seamless transition between shots that were shot on motion picture film to shots that needed to be digital for visual effects. And besides, having three film cameras next to each other on my head would have been too big. There was also the 4K Netflix Mandate, and at that time the Alexa Minis were 3.2K. I’ve done a lot with the Alexa cameras, the Sonys as well, but I decided to compare them to film with the LUT and found that the RED Helium matched best.

Perhaps if we were doing an emulation of regular film stocks, the Alexa would have matched easier, but in this case, with these specific LUTs, we found it easier to match with the RED Helium.

The Minis were chosen for their weight. We needed to make the Three-Headed Monster lightweight enough that it could work as one camera on a fluid head, remote head, or even on a Steadicam. So that’s what dictated what cameras we used and what materials we used to build the rig.

NFS: Did you do anything in-camera or in processing to emulate Kodachrome and Ektachrome when shooting film, or did you stick to the LUTs in both formats to keep it consistent?

Prieto: It was strictly the LUT. I had to take that LUT into consideration when I was lighting because both Kodachrome and Ektachrome added contrast. I used Kodachrome for the 50s, Ektachrome for the 60s, and then for the 70s and 2000s we made a LUT that emulated ENR [A bleach bypass process of the print]. I did it on two different levels. One was a sort of light ENR that reduced a little bit of saturation and added a little contrast to let's say a regular film stock. But once Hoffa is killed I switched to a heavy ENR look. There is even less color saturation and even more contrast.

That's why in the end the film has a sense of desaturation, of course, they're also older and their skin tone changes.

Overall you get the sense that the color has been drained from the image, which is part of the, let's call it “journey,” of Frank Sheeran's character.

I had to take the LUT into consideration in the lighting, of course, but also in the costumes and the set design.We did test out different colors and how a blue suit or grey suit reacted to Ektachrome. For instance, a neutral black suit looks more bluish-green, because Ektachrome introduces a lot of cyan to the blacks.

"Overall you get the sense that the color has been drained from the image, which is part of the, let's call it “journey,” of Frank Sheeran's character."

NFS: In the final third, when it's just Frank, it makes sense that the camera calms down, the scope and influence of the other characters have no reason to be felt.

Prieto: Exactly. It does. And we did not use the Three-Headed Monster for any of that. Once we're with Frank in the Latin casino and beyond it becomes film negative.

NFS: Peggy, Frank’s daughter, is shot differently. We watch her perceive her father’s life.

Prieto: The idea was to isolate her because she is isolated from her father. The scene that comes to mind is when Frank Sheeran steps on the shopkeeper's hand, the violent act in front of his daughter. There again the camera simply pans. It stays in a wide shot. Very simple. Then there's a reaction shot of the daughter.

Peggy is the one moral compass in the movie. She's a judge of it, but it's more in Frank Sheeran's mind in a way. Not in the movie,but in the book, I Hear You Paint Houses. The real Peggy says she never thought her father killed Hoffa or any of that.

They just didn't talk later because they weren't that connected, but there wasn't all that judgment. He thought that she knew; he thought that she was judging him. So, I find that very heartbreaking. In any case, we wanted to represent that notion of Frank's guilt through Peggy.

NFS: Did you light her differently?

Prieto: I don’t think I did anything specifically with lighting. She’s always the one looking, and it’s kind of Frank’s perception of her looking at him. Even in the Latin Casino with Frank and Russo, we do a shot of Peggy looking up at them — so Frank thinks she knows what’s going on...or she’s dancing with Hoffa. One thing I did with lighting was give the scene a red hue from all of these red lamps I asked Bob Shaw, the production designer, to put on the tables, which made it pretty but menacing at the same time.

Anyways, since it was a show and there was a singer, it was an excuse to have a spotlight that could then, while they're dancing, be floating through the dancers and the crowd. I used that to highlight certain moments. I timed it very specifically so that when Peggy looks at Russel Bufalino, the spotlight passes through her, and then when the camera looks at Bufalino the spotlight passes through him, so I wanted to emphasize certain instances with something that seemed random.

NFS: I love that scene in the church where her eyeline creeps down into the bottom left corner of the frame as the film cuts between her and all the commotion.

Prieto: There are two church moments, right? In the first baptism, there are very few people, and then in the second baptism, Frank Sheeran has become part of a group.He’s more popular, more people are there. Peggy’s a witness to this. So, we see her point of view of all these mafia guys. But also the color changes. The first time we’re in this church the color of the lighting is cooler, and then the second baptism is more golden. This is Sheeran’s golden moment, he’s become this more interesting popular man in his mind and in the minds of people around him. So, I wanted a shift in color and certainly that scene specifically deals with Peggy wondering who all these people are. Later she’ll come to dislike that world in contrast to Hoffa, who, like the text says, doesn’t have a name like "Skinny Razor."

"I myself was amazed seeing it all put together. I felt I finally understood it, all of the things we had been doing while we were shooting."

NFS: So when the film does present a “Scorsese” flourish, it’s to signify an energy or motivation that’s other than Frank Sheeran’s?

Prieto: Yes. I’ll give you another example. When Joe Gallo is introduced and we see him going to his senate hearing, we first see him coming through a door. This is a shot Scorsese scribbled and designed in his shot list and made a little diagram. He wanted him coming through the door and to see the people and the cameras, he wanted to introduce him like a rockstar or a celebrity. So, the camera does travel through foreground flashes; I put some TV crews with lights flaring the lens. Then the next shot, during his deposition, the camera swoops down from a big wide shot to a medium shot of him swearing to tell the truth and all that. If it were Frank Sheeran, we would have approached it differently.

There is actually a shot relatively similar to that much later. Frank’s in a courtroom and there’s a lawyer asking him to describe a plan and he’s pleading the fifth. In that shot we did do a boom with a camera towards him, but it’s slower, and at that point the color is different...the ENR desaturated LUT. So there is a similar camera move, but with a different speed and feel to it.

So again, he’s always designing shots. He thinks very rhythmically. He plans the way he’s shooting a movie for the editing.He’s always aware of when he needs to push the energy and bring it back down. I myself was amazed seeing it all put together. I felt I finally understood it, all of the things we had been doing while we were shooting.

NFS: I was going to ask about those recurring crane shots in the courtroom that start wide and then hone in on a character.

Prieto: I think it’s the big picture, seeing the historical context, and then going into the details. That’s the way the movie is. It’s an intimate story with the huge canvas of the history of the United States. I think that’s what those shots represent. It’s saying: "This is a big story, but this is what’s interesting to us within that story."

NFS: There are, let's say, generally two schools of thought on camera movement. Some believe the camera should be stagnant as often as possible. You and Scorsese work with a lot of moves, whip pans, etc. clearly the movement is motivated, but what’s the argument for movement vs. none?

Prieto: By now I’ve done a few projects with him and he really is aware of camera language, and he uses it in a very expressive way. As a cinematographer, I like to play in all of the different modes. I’ve done very kinetic movies, Amores Perros, 8 Mile, or I’ve done things like Brokeback Mountain which are very still and contemplative. I enjoy working with both styles. One of my pet peeves with certain directors is, especially when I’m operating the camera handheld, when they ask me to“Give it energy,” and I’ll say “Wait. I’ll follow the energy.” I think if the scene has energy then the camera will follow and enhance that energy. When the camera is behaving in a way that’s coherent to the characters, the scene, or what’s going on, it just enhances it.

One of my pet peeves with certain directors is, especially when I’m operating the camera handheld, when they ask me to “Give it energy,” and I’ll say “Wait. I’ll follow the energy.”

NFS: Did you have to adjust your approach to lighting the de-aged scenes in any way?

Prieto: Actually, I did not. That was almost a condition that I had with Pablo Helman the visual effects supervisor. I needed to shoot them as if they were that age and not even worry about it. The challenge was making sure the lighting didn't change in the CGI effects and the faces that were placed. They captured the surroundings on the set and the lights. They took a lot of stills from the perspective of the face and color charts and silver ball and grey ball. So for every setup, we had to spend some time to do that. But it was crucial for the computers to map the lighting automatically to the CGI elements so that they weren’t guessing what I did. They were really mathematically and scientifically reproducing it. I must say that was pretty seamless and I was very happy when I started color timing the movie, to recognize my lighting in the CGI and VFX elements.

NFS: Was there any issue retaining the actors’ eyelight in VFX scenes?

Prieto: Somehow they kept their eyes. I don’t know exactly how it all works. Even to me, it’s a mystery. But they really did capture their performance and let their real eyes be there. The window into the soul is real, that’s not CG. We couldn’t see the results as we were doing the movie. We had to wait for them to do all of the visual effects. We only saw it after the movie was edited and months after even. So, it was a big leap of faith and we all trusted Pablo and thankfully it worked out.

NFS: There are a handful of slow-motion vignettes that tend to evoke, more than anything, the sensation of looking back at a well-documented catastrophe in time.

Prieto: We used a Phantomflex camera to get to frame rates that were sometimes around 700 fps or 500 fps. We varied, sometimes less, like 300, like in the killing of Columbo in Columbus Circle. From the very beginning, Scorsese talked about how he wanted to see the expressions of the people. We had a lot of references from that day and the frozen image of their expressions was startling. So I think he wanted to capture that, and extreme slow motion makes it possible to see the instance longer, obviously. It was really to see those expressions as if in a still photograph, but in movement. So, I think that was the impetus for that scene.

"From the very beginning, Scorsese talked about how he wanted to see the expressions of the people."

There were a few others. When Frank Sheeran’s washing his car, Scorsese really wanted to enhance the movement of the tentacles in the car wash. So that was the Phantom, although some of that we shot on film at 48 fps when we see his face going through the wash. Which, by the way, we were not going to shoot him in the car. De Niro felt that it would be better if Frank were inside the car, so then we added that shot tracking with him. So, it’s a little surreal because you see him seeing the car being washed and you see him inside the car as well. It somehow works and it’s actually one of my favorite moments in the film. Slow-motion works because it makes it a little more contemplative and surreal. Sometimes when our minds go someplace else the sensation of time changes. I think that’s the feeling in that scene. It is a tool that Marty uses, and again, he just utilizes everything from the huge toolbox at his disposal.