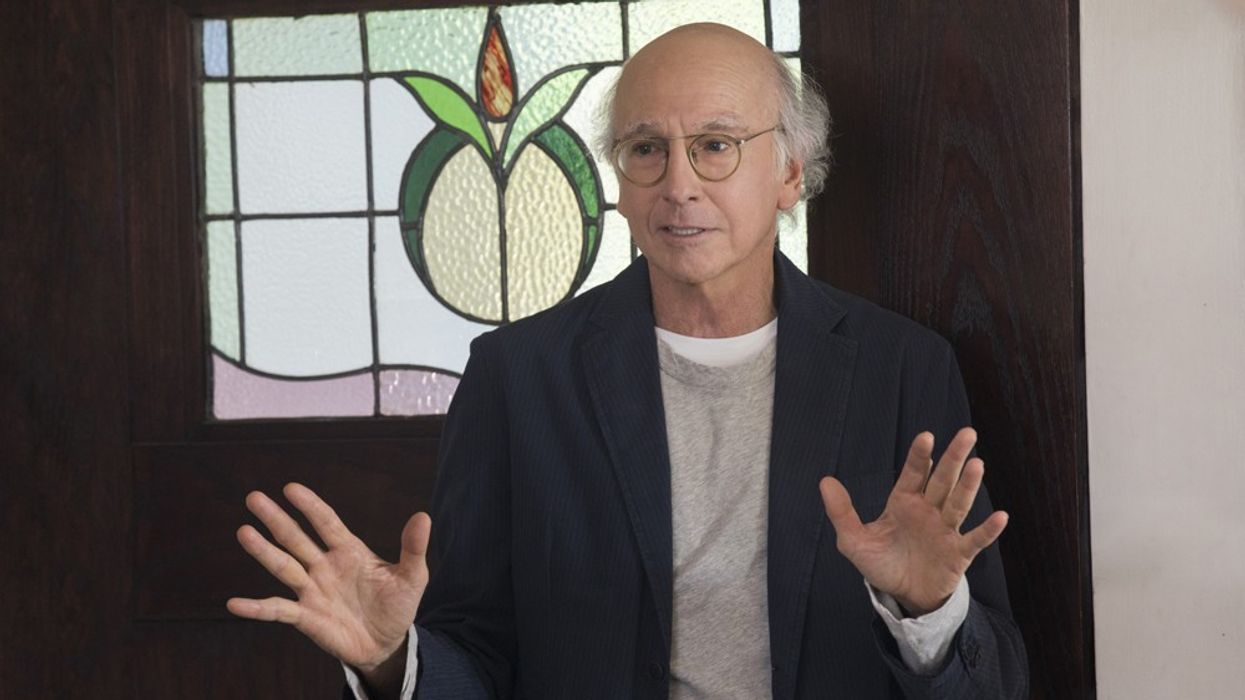

'Curb Your Enthusiasm': How the Editors Find the Comedy in the Show's Unique Shooting Style

Discover the process of cutting the show's signature improvisation into carefully crafted comedic gems.

Curb Your Enthusiasmis back. HBO is now airing its ninth season after a six-year hiatus, and the grudge-holding, socially awkward, fictionalized version of Larry David we've grown to love continues in a ten-episode order.

The new season was split between pilot editor Steve Rasch (3, 4, 6, 8 and 10) and Jonathan Corn (1, 2, 5, 7, 9) who joined in the second season. Interestingly enough, both Rasch and Corn are English majors rather than film students. With a distinguished appreciation for language, they're unique as editors. For them, it's about words and wordplay and how they can carve out an engaging tone from a massive amount of footage.

The comedy's shooting style outlines a rare workflow for the editors that differs from traditional half-hour series. The two sat down with No Film School to share their experience about the Emmy-winning show.

No Film School: Was there any difficulty starting up again?

Steve Rasch: Everyone was wondering how we could get back up to speed story wise, but we justify the change. We didn’t want to pretend it was the next month. On a technical level, it was a little bumpy as Curb has a shooting style that's not easy for the crew.

NFS: In earlier seasons, the show was 4:3 in standard definition. It’s gradually changed overtime. Are they shooting 4K now?

Rasch: We do shoot 4K UHD, but we master in HD—the current HBO delivery format. We are using Sony cameras that have a much sharper look. Larry has always been a low-fi guy. We were standard definition with the bars on either side for a while. I remember a funny conversation saying to Larry that we have to go to HD. He always thought the comedy played better in 4:3, but we dragged him into it and now he sees the benefits of higher resolution.

NFS: Do you apply any look with the new cameras?

Rasch: The ideal look would be 16mm film. A format that’s not too sharp. In the early years, we applied a film affect to the video to bring down the harshness to make it look closer to a film. Now we don’t have to do too much to treat it. Our colors are a muted, natural palette.

"Larry is a genius improvisor, and he can be funny in the moment, while at the same time, he has the story beats of the outline in his head."

NFS: Instead of a traditional script, episodes are shot using an outline where actors improv scenes. How does this kind of on-set freedom affect your edit?

Jonathan Corn: Editorially, it’s a lot of fun because it is just an outline. Our cast has the freedom to go off in various directions and no good idea goes unexplored. No matter who it comes from, they will keep working that idea whether it’s one take or several.

The outline does a great job laying out what we need in a scene, but there’s looseness to the way they shoot it. As an editor, we pluck together the story information and the best jokes or nuances in each take to try to put together a coherent scene in the funniest way possible.

Rasch: Other comedies have tried this improv/outline style. It usually fails as improvisation is a skill that most actors do not necessarily possess. Curb tests most of the talent in an audition—even an established actor. Additionally, Curb succeeds because Larry is a genius improvisor, and he can be funny in the moment, while at the same time, he has the story beats of the outline in his head. He can steer the improv back to the essential story beats, while he's improvising. Not easy. But if something original pops up in take four, Larry will make sure to explore that topic. Sometimes these incidental improv additions become classic Curb moments.

NFS: We’re guessing that means you have to watch all the dailies?

Corn: Exactly.

Rasch: Yes.

NFS: Do the outlines steer the comedy?

Rasch: The outline has funny beats, regardless of where the dialogue is going. So if the improv is not particularly clever, I cut the scene tight to the essential story beats in the outline. It's okay to just move story along. There is no "jokes-per-page" requirement.

NFS: So in a way, you’re editing a documentary where instead of looking for “starred” takes from a script supervisor’s script, you’re watching all the dailies to find the best story.

Corn: Certainly. The show itself has a very documentary feel to it.

NFS: How do you approach episodes then?

Corn: In my first cut, I’ll try to find the best stuff, and in the second pass find what serves the overall season arc. Sometimes story points will come out of nowhere that will end up being an episode arc. They will discover them while shooting, and they will be great for that episode, but it won’t affect the season.

Then as we go through the edit with Larry and series director Jeff Schaffer, we realize what points we need to make in the episode or it’s not going to make sense when something comes up later on in the season. We try to keep an episode as contained as possible so it can be enjoyed on its own.

"My goal is to make great sentences, not great edits."

Rasch: For me, I approach it more from an audio perspective. My goal is to make great sentences, not great edits. When people improvise, there are inappropriate stammers and pauses. Comedy has to have the right timing or it fails. We spend a lot of time making it sound good as it if was written that way. Because it’s not, we try to make the dialogue flow. Good comedy has to be quicker than most people speak so we are taking a lot of the empty air out.

NFS: Does the shooting style of the show dictate what you can do with the edit?

Rasch: The main ingredient that allows us to do what we do in the editing room is the two opposing cameras. One on Larry and one looking over his shoulder to the opposing person he’s arguing with. Most of the comedy of the show comes from the back and forth. From the pilot, we decided we needed two cameras all the time shooting simultaneously so we can take out the pauses and still have it match.

NFS: Curb also has a ton of overlapping dialogue which you don’t hear in many shows. Is that something you’re building into scenes or does that come from set?

Rasch: It’s something Larry fought for from day one. Most actors are taught not to do it and then editors can overlap later on if they want to, but Larry wanted a natural overlapping feel on set. He didn’t want to hinder people’s impulses since everyday conversation has overlap.

Rasch: You learn what words you can cut on pretty quickly. S, T and P are great syllables to cut on when you’re combining two takes of the same sentence. Then we let dialogue run on people’s back. We also do a lot of repair work right in the editing room with Larry and a microphone.

And if you’ve ever watched Seinfeld and hear a piece of story played over the window of Jerry’s apartment, they most likely lifted part of a scene out. We do that trick when we try to shorten the show and need to delete scenes.

NFS: Going back to doc-feel. When you watch Curb episodes, there isn’t much cutting to b-roll. When that tool is kind of taken away from you as editors, how do you work around the trouble spots in scenes?

Corn: At times, you wish you had something to cut to because it would be convenient editorially, but at the same time, one of the challenges is not having that thing to cut to. Because Curb has a docu-feel, the more you place in inserts and traditional comedy pieces, the less grounded it gets. It’s not to say we don’t use them, we just try to make sure they don’t stick out in any way that would be odd. By and large, it’s about creating a fly on the wall feel for audiences.

"When we’re editing, Larry isn’t afraid to let a moment go silent or let it sit in a reaction."

NFS: A lot of the comedy surrounds Larry David’s character. How do you look to play story points off him in the edit?

Corn: One of my favorite things about the show is that it’s based on people reacting to Larry or the situation he caused. When we’re editing, Larry isn’t afraid to let a moment go silent or let it sit in a reaction. We make sure you can always hear what he is saying but it’s frequently fun to watch people react to him and build a rhythm of a scene of people’s faces reacting to what Larry is doing. We have complete license on this show to do that.

Other comedies can be driven by talking heads—people want to see the eyes of the mouth at the time the words are being said. On Curb, we can try and find a more natural flow to the conversation. That’s where I think the comedy comes from instead of the standard setup punchline approach.

Corn: He’s very collaborative and seems to enjoy post very much since it’s kind of a continuation of the writing. It’s not a stressful situation at all and it’s really enjoyable, but you have to be on your toes. We get a lot of notes as our first cuts tend to be around 45 minutes to an hour long which we have to condense later on.

Rasch: Larry is mostly looking at the comedy and the story. He wants to dissect and see every take before moving forward. Larry is a master of preserving the show’s tone. If bits sound "jokey" or "written," they usually don’t survive, even if we are getting huge laughs in post. If I could put a post-it on my keyboard to keep me on track, it would say "keep it real."

NFS: That begs the question how long does it take to get through an episode?

Rasch: We wouldn’t want to cut this show on a network schedule where we only have seven days to put it together. We need about three weeks to do a 45-minute first cut. It gives us the time to do it right. It’s a rewriting process just as much as an edit. Larry understood this very early on and allotted the time so we don’t have air dates creeping up too early.

Rasch: Larry first heard the eventual theme music, “Frolic,” composed by Luciano Michelini, in a bank commercial. He asked his assistant, who is still working for him, to track down the music. She found it at Killer Tracks who bought the library from RCA. We got a whole box of 15 CDs from this collection. The discs had a wealth of sound to it—this circus pit orchestra that was truly unique. It was recorded in Italy for TV in the 60s and 70s. I ended up getting the gig as the music supervisor and have been doing it ever since. 95-percent of the music in Curb is pre-recorded library music.

NFS: How do you like to work with the music in the edit?

Corn: I usually build my edit first then lay in the music. It’s always going to make something better so I don’t want to cheat by putting the music in because it is so recognizable. I feel like if I did that first it would let me skate by a little bit.

Rasch: The music is sort of our laugh track. The show deals with some heavy arguing and tense topics and the music is our tool to bring the mood back up and cue the audience to laugh. It’s an enjoyable circus track that has good energy and kind of counterbalances the intense discomfort created by Larry David’s character.

NFS: Can you share a piece of advice from editing Curb?

Corn: One thing I learned on this show is you might be able to use something for anything so you better watch everything.

Rasch: Aspiring comedy editors should watch a lot of standup comedy, both on TV and in clubs. Learning how the rhythms of a stand-up comedian work is an invaluable experience. Watch the masters at work on stage, and carry that to the edit bay. Every comedian has a different approach to timing. But there are a lot of similarities in how a good joke is structured. Surprise is key. And an emotional truth within the joke.